The discussion of the theory and practice of Ongkāra (Pranava; Oṃ) in the Balinese Tantric Yoga tradition has been described in the previous article. This article is a follow-up to the previous article, which will discuss further Ongkāra and its relation to Tantra, Mantra, and Yantra. As is well known, discussion of Tantra is usually accompanied by discussion of Mantras and Yantras, so the three often become topics. In this paper, I would like to describe how these three concepts in Bali lead to a single topic — the discussion of Ongkāra.

In various traditional Balinese manuscripts called lontar (palm-leaf manuscript), the Ongkāra mantra is often referred to as Wongkāra, which means human-maker. This means that Ong is the same as the human himself. Apart from being implied in the term, various straightforward explanations related to this topic are also widely distributed in various lontars in Bali.

Tantra, mantra, and yantra, all lead to Ongkāra. In other words, in Bali, the discussion of the Tantra, Mantra, and Yantra boils down to the mystical values of human beings.

Tantra, Mantra, dan Yantra

Tantra

The word tantra in its modern context has many connotations, and many of them are confusing, even leading to misunderstandings. For most people in the global community (as can be seen in Google search results), Tantra means “sexual yoga.” Tantra is even associated with a type of sensual massage (tantric massage).

Maybe this view is rooted in (at least) two misunderstandings. First, is the over-generalization of maithuna rituals (rituals that involve sexuality). Maithuna is indeed listed in traditional Tantric literature, but only a small part of it. Unfortunately, in the global view, this ritual is seen as the totality of tantra itself. Second, it seems that there is confusion in distinguishing tantra from the Kāma-sūtra (lit. aphorism of love). This has resulted in people associating Tantra with sexual pleasure.

In addition to the fallacy of this modern view, there is also a traditional misconception about Tantra. For example, in Colonial India, the word tantra was synonymous with “magic,” specifically “black magic.” Many tantric texts discuss and teach the cultivation of supernatural powers indeed, but (again) Tantra is not just about that.

The lexical definition of the word tantra is book or scripture. In the beginning, the word tantra could be used to refer to any book. However, later the word tantra was more widely used to refer to a group of literature from Mantramārga canons. Therefore, there is often an association that “tantra is the same as Śakta” (followers of goddesses; adherents of the feminine aspect of the Divine). Of course, there is Tantric literature that follows the Śakta lineage, but there are also tantras from the Śaiva, Vaisnava, Bauddha, and other sects. Various other terms that can be used as synonyms for the word Tantra (in the sense of the literature genre) are Sutra, Samhita, and Agama.

As a literary canon, tantra is seen as independent of the Vedas because it does not perform the rituals prescribed by the Vedas, nor does it use Vedic priests (Brahmins) as ritual leaders. Therefore, it is stated that in the Dharma tradition there are two types of revealed literature (shruti), namely Vaidika (Vedic literature canon) and Tantrika (Tantric literature canon).

Although Veda and Tantra are seen as two distinct streams with unique characteristics, they also influence each other. So, there are things that are discussed in the Vedas that are also discussed in the Tantra, and vice versa. However, whilst the subject of the discussion may be the same, the description is not necessarily the same. For example, all dharma traditions have discourses on ātma (the soul), but each tradition has a different understanding of what ātma is.

In the Balinese tradition (text and context), the word tantra is only used a few times to refer to literature or teachings. However, the word āgama, which is a general term for the Śaiva-Siddhānta scriptures (Siddhānta-tantra) is frequently used. The religious teachings in Bali are classified as Śaiva-siddhanta by scholars. The Śaiva-siddhanta texts are texts that are categorized as “right-handed tantra.” So basically, regardless of the term used, it can be said that Bali is the land of Tantra.

The Śaiva-tantra texts in Bali are better known as Tattwa/ Tutur manuscripts. The discussion in that manuscript category is about tattwa (the essence of existence). Apart from these “right-handed tantric” texts, there is also the lontar genre known as Kawisesan which teaches about various types of “magic” as is common in “Left-handed Tantra” literature.

Mantra

Tantra is often called mantra-śāstra because it often focuses on discourses of mantras. The discussion of mantras in tantric literature is not only related to “prayers” and “praises” but mantras are explored from various sides, i.e. symbolic, pragmatic, and mystical aspects. This is what distinguishes the discussion of mantras in the Vedic scriptures from Tantric literature. The discussion of mantras is also inseparable from the discussion of śabda (sound) and letters or syllables (akṣara).

From the pragmatic aspect, mantras are syllables, words, sentences, or stanzas that are chanted. Its function can be as a form of prayer or praise, it can also be a meditative tool (repeated in japa to focus the mind on a single object). Mantras are also said to invoke gods or goddesses, to gain certain powers, or for other specific purposes.

In Tantra, there are discussions about Sat-Karma (6 types of magic). Broadly speaking, of the six types of magic, some are constructive and some are destructive. However, regardless of their purpose, all types of magic use the power of mantra (and yantra).

In this context, mantras function as a medium of communication between humans and the innate self, natural forces, and divine powers – a mantra is a communication device. In daily life, we communicate through regular words and language that both sides can understand, and in metaphysical communication, language is a mantra.

However, apart from being a medium of communication, in Tantra, mantras are also applied in other ways, such as mantra-nyasa, which is the practice of placing a mantra on a certain part of the body. In this context, a mantra is not merely a communication device, but some kind of energy. The pragmatic side of the mantra also acts as a ritualistic and meditative tool.

Then there is the symbolic aspect of the mantra. In this context, we can find various discourses on akṣara (letters, syllables). Each akṣara signifies a different level of consciousness, a different dimension of reality, different gods, and many other connotations.

Before proceeding further, it will be necessary to bear in mind the differences between signs and symbols in Jungian Psychology. As a sign, a mantra does not only need to be chanted, but it is necessary to understand the meanings it represents. As a sign, the mantra works at the level of the conscious mind to bring understanding and a medium for contemplation. Meanwhile, as a symbol, the mantra works at the level of the subconscious mind, to present the “feel” of the collective understanding it represents.

Mantra as a sign represents a pragmatic aspect, especially for cognitive purposes. While the mantra as a symbol represents the mystical aspect, the purpose of which is to “establish” understanding from the deeper side of the mind to the cognitive dimension. Mantra as a symbol is a way to bring the pearl of understanding hidden at the bottom of consciousness to be understood by reasons – from the unconscious to the conscious.

The pragmatic and symbolic aspects of the mantra then lead to the third dimension, the mystical aspect. A mystic is one who seeks union with the Divine. There are two important things from this definition; there is a goal to be achieved, and there is a way to achieve that goal. The goal and the path to be achieved have been mapped out through the symbolic aspect of the mantra. While the vehicle to achieve this goal is to use the pragmatic aspect of the mantra.

The experiences to be achieved are transcendental and non-dual experiences. Transcendental means beyond human experience (the experience of body and mind), and non-dual means experiencing the unity and wholeness of all existence, both visible and invisible.

From the mystical-metaphysical side, a mantra is not just a sound or a collection of letters that make up a word. In the view of the Tantrikas, a mantra is a living entity, it is real energy. Mantras are sonic bodies of certain deities. When a person chants a mantra or puts a certain mantra on a part of his body (nyasa), then for him it is a way to fill the body with the divine power that the mantra represents.

Yantra

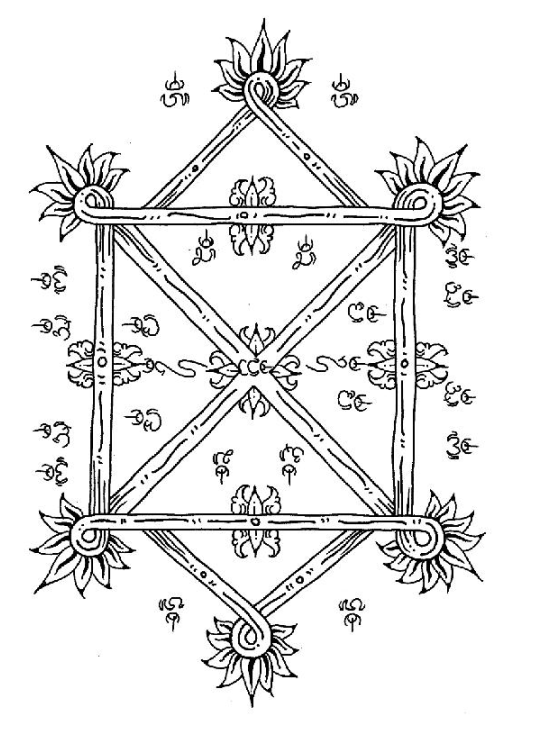

The word yantra means tool or machine. Yantras are commonly known as sacred geometric diagrams drawn on paper, metal, or sculpted on other media. In addition to geometric diagrams, Yantra can also consist of certain images—ranging from images of anthropomorphic entities, gods, giants, animals, or certain symbols. Yantras can also consist of inscribed mantras.

Yantra is also referred to as Chakra. For example, one of the most famous Yantras, Śrī Yantra, is often also called Śrī Cakra. So, today’s conception of chakras (which are understood as subtle energy centers in the body) were originally shrines for certain deities. Yantras are also referred to as mandala. With regard to differences between the yantra and mandala, in this writing, we will use the definition of a mandala as a shrine of the gods and a yogic tool.

Like a mantra, Yantras have many uses. Some Yantras are designated as the shrine of the gods, and some yantras are intended to achieve more personal aims; from winning in war, succeeding in business, conquering competitors, winning the hearts of loved ones, and much more. There are even yantras devoted to destructive purposes, such as hurting others. In one of my books, Ensiklopedi Kiwa Tĕngĕn, I collected various types of Balinese Yantras/ Rajahs from various lontars.

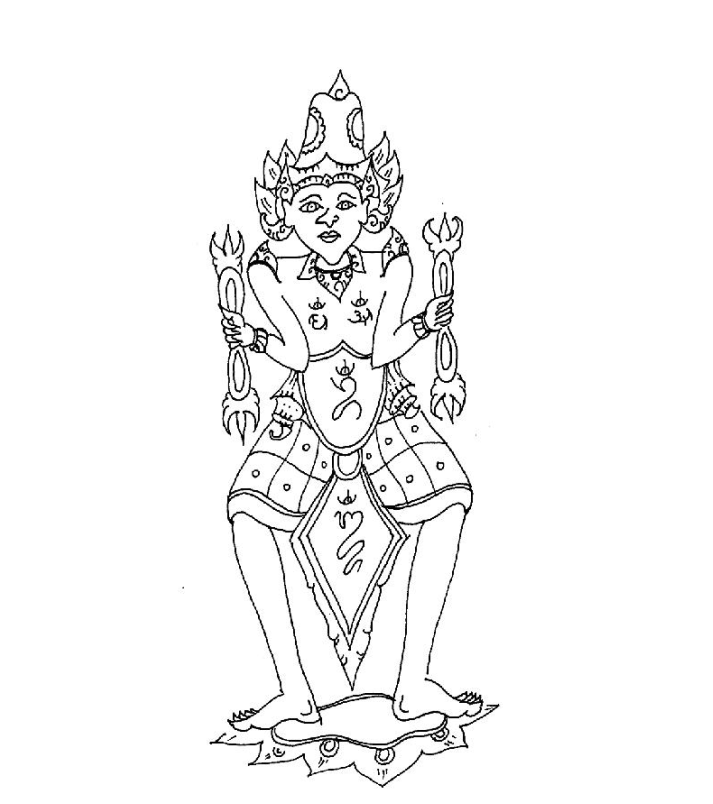

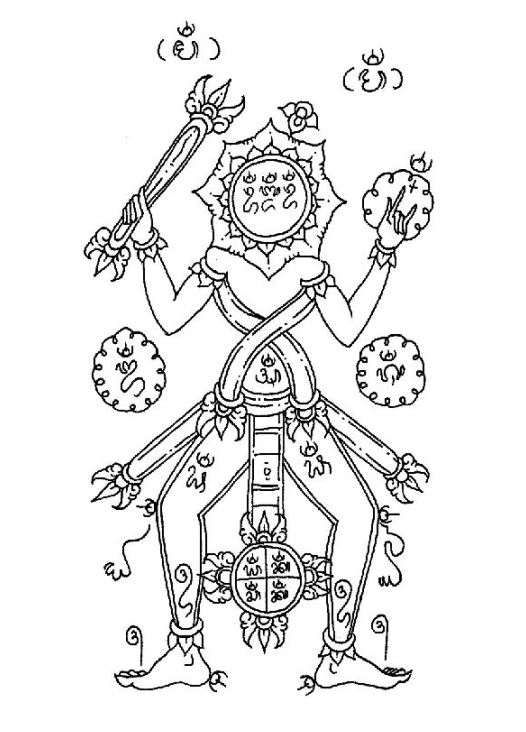

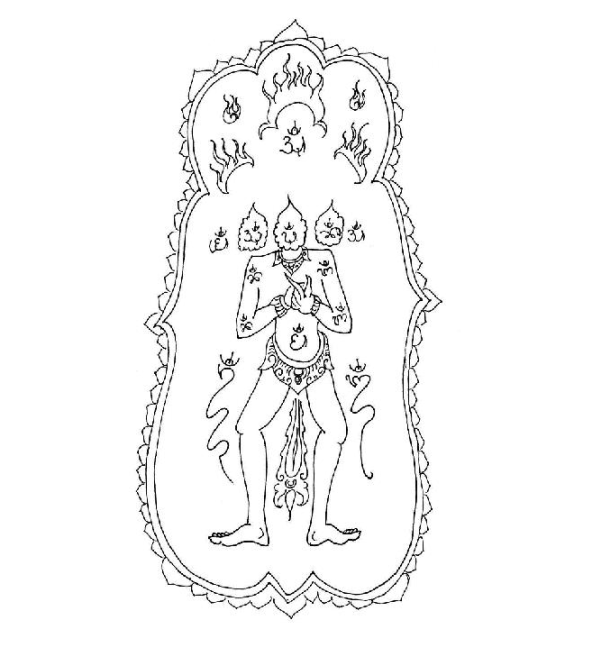

In the Balinese context, yantras as geometric shapes that are popular in India are not widely known. However, in Balinese tradition, Yantra is very widely used in its form as a picture of a figure or inscribed mantra. In Bali, this type of Yantra is commonly referred to as Rerajahan.

Rerajahan is an inseparable element of Balinese religious life. In various rituals, certain rerajahan is made (either on paper, cloth, or metals), then placed together with the offerings. In houses or sacred buildings, various kinds of rerajahan are usually made, then hung. The most common image of rerajahan is Ongkāra with its various variations.

Then Yantra as a mandala in Bali is also widely applied, both empirically and metaphysically. Empirically, the concept of mandalas is applied through buildings and spatial planning. Both the construction of houses, sacred places, and local village layouts follow the mandala concept.

The main temples in Bali are also seen as mandalas. Each temple represents one cardinal direction. For example, the temples that are classified as Pura Padma Bhuwana (The Temples of Cosmic Lotus), are 9 temples located in 8 cardinal directions plus 1 in the middle. In the 9 cardinal directions also lie the gods and their own Akṣara, all of which also have their place in the human body. This shows that nature and the human body are a kind of fractal mandala.

Here are some examples of yantra (rerajahan) in Balinese tradition:

Human Being As Ongkāra; Ongkāra As Tantra, Mantra, dan Yantra.

Human Being As A Scripture

As can be seen in the previous article, the mysticism of Tantra Yoga in Bali revolves around Ongkāra, both in his role as Tantra, Mantra, and Yantra. As Tantra (scriptures), it is stated that Ongkāra is a book of life. Hence, understanding Ongkāra is understanding every aspect of life itself—the real nature of everything, every layer of existence, and all its dynamics.

Broadly speaking, Balinese people strongly believe that life consists of two layers, i.e., sakala (physical) and niskala (metaphysical). In a more specific explanation, Ongkāra contains the description of tattva (layers of existence).

Empirical reality is a reality that exists within the boundaries of space and time. While the metaphysical reality is a reality that transcends the boundaries of space-time. Both these realities are represented by the two parts of Ongkāra; Uluchandra as niskala, and Wiswa as sakala. [For further explanation, please read the explanation in the following article to understand the anatomy of Ongkāra].

As mentioned before, the “Ongkāra” is often written (and pronounced) as “wongkāra.” The word wong means human being in Balinese and Old Javanese. While the word kāra means; a doer, maker, causer, doing, making, causing, producing. Loosely, wongkāra means “that which makes humans exist.” In the Gaṇapati Tattwa, it is stated that “there is no difference in the origin of the appearance of humans and devas, namely Ongkāra.”

Another manuscript stated that humans are “living books (janma pustaka).” To put it simply, humans are Tantra. In another term that is more widely known to the Balinese people, humans are referred to as “letterless manuscript (lontar tanpa tulis).”

This implies that within ourselves have written various kinds of understanding and wisdom. If extracted from the explanations in the Tattwa/Tutur manuscripts, this is of course because the essence of human being is Śiva himself (Śiva-tattwa). As mentioned in the Tattwajñāna Manuscript, the light of knowledge (jñānaprakaśa) is the embodiment of Śiva himself.

Unfortunately, knowing that humans are “the true scriptures” doesn’t necessarily mean we can read them. Learning to read this scripture called the body requires its practice. The practice of reading the true scripture is done by cleansing the mind of various impurities. In traditional terms, training the mind to be crystal clear (sphatikajñāna). Ongkāra as a clear state of mind is referred to as Ongkāra-śūddha in the Lontar Gaṇapati Tattwa. Borrowing from Mpu Kaṇwa’s parable (in The Arjuna Wiwaha Kakawin), only a jar with clear water can show the reflection of the moon. If the water in the jar is muddy, dirty, and weavy, there is no clear reflection appears. Likewise, when the mind is clear, inner wisdom begins to be realized.

In the depths of the consciousness, the content written is about self and life itself. We repeatedly go too far on a journey to find ourselves, whilst the answer lies within. Concretely, for example in the practice of meditation, when the turmoil of the mind (cittavṛtti) begins to calm down, then we can see ourselves more objectively. We can see our thoughts, feelings, and behavior through clear eyes.

Human Being As A Mantra

Human is a living mantra—breathing and walking mantra. As discussed earlier, mantras have pragmatic, symbolic, and metaphysical aspects. To say that human is a mantra is to state that the three aspects of the mantra are also an inherent part of a human.

Traditionally, one of the key points of discussion about yoga in Bali is related to shabda (sound/words), bayu (breath/movement of life), and iḍĕp (mind-feeling). These three aspects of human beings are manifestations of the mantra AṂ, UṂ, and MAṂ. In the practice of Yoga-akṣara, these three mantras/akṣara are then transformed into Ongkāra. Uniting the sound-breath-mind means focusing the consciousness on a single point. This also means a human is a mantra (wongkāra) when his/her mind is concentrated.

To see humans as a mantra also implied that through Ongkara (which are the essence of all mantra) every aspect of the human being can be understood. There are many types of Ongkara in Bali, as I have also written in the article Philosophy and Practices of Ongkara, and in more detail, in my book, Ilmu Tantra Bali.

Akṣara AṂ-UṂ-MAṂ is the result of the transformation of the Five Akṣara Brahma (pañca-brahma), namely SA-BA-TA-A-I. The five are often identified with the five basic elements that make up the human body (and the entire universe) i.e. pṛtiwi, apah, teja, bayu, and ākāśa. Thus, the entire human body is constructed by this five akṣara. These five Brahma scripts are added to the five Śiva scripts (NA-MA-ŚI-WA-YA) to form the Daśa Akṣara, also known as Daśa Bayu by some lontars, namely the ten powers of human life.

Then the AṂ-UṂ-MAṂ transforms into two akṣara called akṣara-rwabhineda, namely AṂ-AḤ. Both are symbolic aspects of the breath; AṂ is the breath in, and AḤ is the breath out. They are also often used as symbols of the sun and moon, fire and water, matter and consciousness. Then, these two Akṣara (AṂ-AḤ) transform into an “undivided-two” called Ongkara Adu Muka , namely standing and upside down Ongkara which become one.

Such is man as a mantra in its symbolic aspect. Pragmatically, mantra is a spiritual path. Therefore, to say that “man as a mantra” is to state that human life is a spiritual path. Whatever we do in life, it is all a journey of transformation of consciousness. Our life is a mantra that chants all the time.

Through the breath, we always chant the AṂ-AḤ mantra. Thinking, moving, and breathing means we are using the AṂ-UṂ-MAṂ mantra. Our whole gross body is built up by the mantra SA-BA-TA-A-I. Our two most subtle components are Ongkara-standing and Ongkara-inverted. Hence, once again, humans are a living mantra.

Human Being As A Yantra

Because humans are a manuscript, within humans, there are various kinds of akṣara. For this reason, one of the most popular yoga practices in Bali (both textually and contextually) is placing (nyasa) various akṣara on the body. In Balinese Tantric tradition, The Nyasa Practice can be seen as a way to transform a body into Yantra.

Each akṣara has a place in one of the cardinal directions, then also in the body. As can be seen in the following table:

| SCRIPT | MICROCOSMOS | MACROCOSMOS |

| SA | East | Heart |

| BA | South | Liver |

| TA | West | Kidney |

| A | North | Bile |

| I | Center (1) | Center of Liver |

| NA | Southeast | Lungs |

| MA | Southwest | Colon |

| ŚI | Northwest | Spleen |

| WA | Northeast | Throat |

| YA | Center (2) | The edge of liver |

From the table, it can be seen that Akṣara is the bridge that connects the cosmos and the body. At the same time, akṣara also makes humans and nature a unified mandala.

Conclusion

Balinese spiritual tradition can be summarized in one letter, namely Ongkāra. Ongkāra is tantra, mantra and yantra. As tantra, Ongkāra is the library of life itself. As a mantra, Ongkāra has a symbolic aspect, which is a vehicle for conveying meaning about the nature of human existence. Ongkāra also has a pragmatic aspect, through which all the theories described can be experienced. Meanwhile, in the mystical-metaphysical aspect, Ongkāra is the experience of Śiva-hood itself, both in terms of sakala and niṣkala. Ongkāra is also referred to as Wongkāra, which means human. Therefore, it can be concluded that humans are tantra, mantra, and yantra.

Although they seem different, the discussion about tantra, mantra, and yantra is one unit. Tantra is a genre of literature that teaches a lot of mantras and the essence of life (tattwa). Likewise, the mantra is “literature” unto itself; it has an ontological side that embodies the same description as the description in tantric literature and also has an epistemological side (through which theory can be experienced). A yantra is a “visual” implementation of tantra and mantras.

The three of them were never separated from one another, regardless of the terms being used. Likewise in Bali, even though these terms are not very popular in the context of tradition and literacy, their implementation is an inseparable part of Balinese people’s lives.

Thus this discussion presented as a reminder of the divine nature of human beings and all life.